How to Help Your People Thrive in Uncertain Times

First published on Inside Retail as ‘Languishing in the time of COVID’

By Dr Sarah Cotton

Imagine it’s the year 2031. Coronavirus is a distant memory. The vaccine has successfully been rolled out and life (for the most part) is back to ‘normal’. Looking back, how will you remember feeling at this time? Maybe exhausted? Somewhat grateful? Often Stressed? Or a bit well, ’Blah’?

Chances are, like many of us, you’ll be experiencing a range of these emotions, often simultaneously. COVID-19 has upended our lives in unprecedented ways, and as the crisis is still unfolding, we’re yet to fully comprehend its impact on our mental health and wellbeing.

Many workers have experienced a decline in mental health since the pandemic began, and for Australia’s 1.5 million retail workers it’s been an especially bumpy ride.

The ongoing fear of COVID-19 transmission and increase in customer aggression and abuse has seen a dramatic rise in workplace safety issues and created mental health challenges for the country’s second-largest workforce.

Last year retail workers reported a 400% rise in customer aggression and abuse, according to a report from the National Retail Association. With lockdown measures in place across most of the country, Woolworths CEO Brad Banducci has this week called for calm by publicly asking for kindness for staff working on the “front line” in stores or delivering groceries.

A snapshot of mental health and wellbeing in the Australian retail workforce commissioned by SuperFriend, shows retail jobs have become increasingly stressful. It reported that 2 in 3 retail workers have experienced a mental health condition; the second-highest proportion of any industry.

The environment is rapidly evolving with no clear end in sight. The bridge between our ‘old normal’ and ‘new normal’ is going to take an uncertain amount of time, and we’re not sure what’s on the other side.

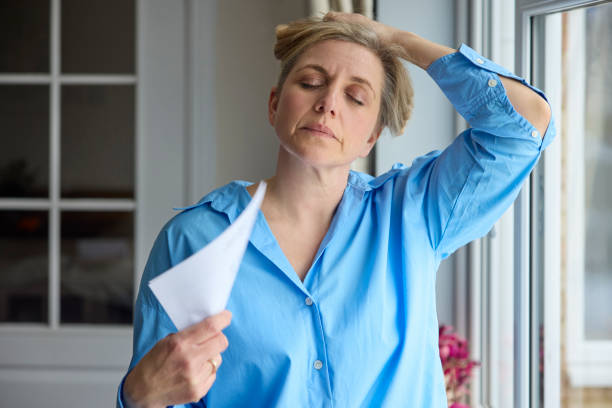

For most, there has been a lot of life changes in a short space of time and feeling a sense of restlessness, unease or an overall lack of interest in life or the things that typically bring you joy is just one part of this. We now have a name for this particular emotion; languishing.

What is Languishing

In a recent article for The New York Times, psychologist Adam Grant drew the connection between Languishing (first defined 20 years ago by sociologist Corey L. M. Keyes) and COVID-19. Grant describes languishing as “a sense of stagnation and emptiness. It feels as if you’re muddling through your days, looking at your life through a foggy windshield.” When you’re languishing you’re neither mentally ill nor mentally healthy, you’re essentially existing in this in-between state.

With the sustained threat of the pandemic over the last 18 months, we’ve been operating in a heightened state of anxiety with little reprieve. While Australia looked to be on top of the pandemic early, we’re now experiencing a resurgence of cases leading to feelings of anxiety and frustration. Currently millions of Australians, are currently under stay-at-home orders to limit the spread of the highly contagious Delta strain. Most states and territories have once again reintroduced border and travel restrictions, throwing long-awaited holiday plans into chaos and despair for those unable to spend time with loved ones interstate. It’s no wonder many of us are languishing.

Languishing dulls our motivation, disrupts our ability to focus, and stops us from functioning at full capacity. If left unaddressed, it can lead to more serious mental health conditions. For example, research shows healthcare workers in Italy, who were languishing, were three times more likely to develop post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in the wake of Covid-19. Research by Corey L. M. Keyes found that the risk of major depression in languishing adults is six times more likely than flourishing adults.

With 7 in 10 professionals already suffering from burnout in the wake of the coronavirus pandemic, we not only have an opportunity but an obligation to create a mentally healthy environment in the workplace.

According to research by PwC, rates of depression, anxiety, suicide and self-harm in Australian workplaces continue to rise at an alarming pace. Their report on mental health in the workplace looked at the financial cost incurred when employers don’t take action to address and manage mental health conditions in their businesses. It estimates the cost to Australian business is approximately $11 billion per year.

The case for helping your people thrive

Organisations need to implement systems and policies that support employee entitlements around mental health and wellbeing and develop a culture where psychological safety is proactively encouraged. The case for investing in mental wealth is not only good for society, it’s good for business. Research by PWC shows that Australian companies can reap $2.30 for every $1 spent on workplace mental health strategies.

COVID-19 has been instrumental in opening up important conversations about mental health and wellbeing in the workplace, and employers are recognising that the demands on individual workers are ever-changing. It’s been encouraging to see the many changes that have come about from the challenges that businesses have faced (and continue to face) as a result of the pandemic.

We have spoken with many leaders who are looking to utilise this opportunity to create change within their organisations. This group wants to place a greater focus on holistic employee wellbeing moving forward by developing strategies that include a better balance of work-life responsibilities, an increased focus on psychological safety in the workplace, and the creation and implementation of strategies to ensure they are taking a prevention-led approach.